6 March 2015

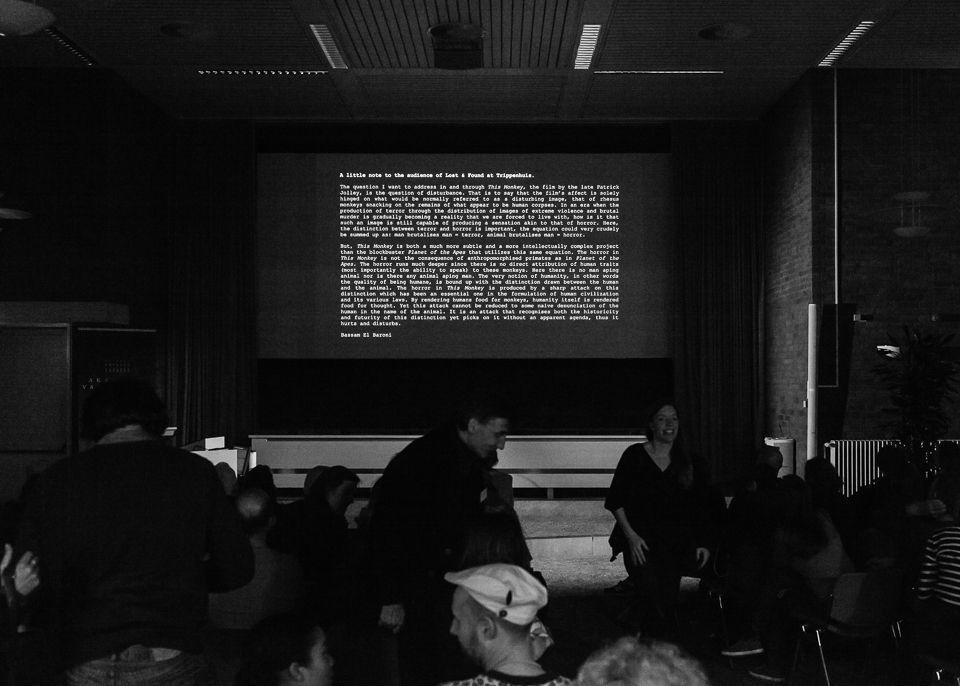

This Monkey will be presented at Lost & Found, an evening of performance and screenings at Trippenhuis. Lost & Found is a night of stray images and sounds, where artists, scientists, writers and musicians present work. This Monkey will be introduced by a text written for this occasion by Basam el Baroni.

Contributions by: Irma Boom, Shirley Berends-Montero, Cécile B. Evans, Maarten Kleinhans, Simon Wald-Lasowski, Peter Zegveld.

This Monkey

The question I want to address in and through This Monkey the film by the late Patrick Jolley is the question of disturbance. That is to say that the film’s affect is solely hinged on what would be normally referred to as a disturbing image, that of rhesus monkeys snacking on the remains of what appear to be human corpses. In an era when the production of terror through the distribution of images of extreme violence and brutal murder is gradually becoming a reality that we are forced to live with, how is it that such an image is still capable of producing a sensation akin to that of horror. Here, the distinction between terror and horror is important, the equation could very crudely be summed up as: man brutalises man = terror, animal brutalises man = horror. But, This Monkey is both a much more subtle and a more intellectually complex project than the blockbuster Planet of the Apes that utilizes this same equation. The horror in This Monkey is not the consequence of anthropomorphised primates as in Planet of the Apes. The horror runs much deeper since there is no direct attribution of human traits (most importantly the ability to speak) to these monkeys. Here there is no man aping animal nor is there any animal aping man. The very notion of humanity, in other words the quality of being humane, is bound up with the distinction drawn between the human and the animal. The horror in This Monkey is produced by a sharp attack on this distinction which has been an essential one in the formulation of human civilization and its various laws. By rendering humans food for monkeys, humanity itself is rendered food for thought. Yet this attack cannot be reduced to some naive denunciation of the human in the name of the animal. It is an attack that recognises both the historicity and futurity of this distinction yet picks on it without an apparent agenda, thus it hurts. Remember if you will the film Alive (1993) depicting the real-life story of a small group of survivors who escaped death after their chartered aircraft crashed into the Andes mountains between Chile and Argentina in 1972. Stranded for over seventy days in the most austere of sub-zero temperature environments they could only survive by feeding on dead fellow passengers who had been preserved in the snow. Dr. Roberto Canessa, one of only sixteen survivors of this incident was only nineteen at the time. In a recent interview he recalls the experience of having to eat a friend: “It was repugnant. Through the eyes of our civilised society it was a disgusting decision. My dignity was on the floor having to grab a piece of my dead friend and eat it in order to survive. […] But then I thought of my mother and wanted to do my best to get back to see her. I swallowed a piece and it was a huge step – after which nothing happened.” We are only one contingent accident away from having to do the same as Dr. Canessa and the rhesus monkeys in Jolley’s film. This tells us that the idea of humanity as we have come to know it is based on a trauma which is that of the inability to wrest away the animal from the human. This Monkey is a confrontation with this trauma and thus a disturbance, for some a deep horror. Through the trauma’s sophisticated theatrical staging and dramatisation the film demands a more realist approach to the idea humanity.

Bassam el Baroni, March 2015

Visit Website Lost & Found